A Review of "Transient and persistent representations of odor value in Prefrontal Cortex"

Olfactory stimuli in natural scenes are very complex due to their high dimensionality, strong context-dependence, temporal dynamicity and variability. Yet species across the animal kingdom use odours to learn associations of rewards and punishments to their advantage. It becomes an exciting question to decipher how animals can build odour representations in their olfactory circuits and combine them with different reward signals to execute learnt behaviours. Pursuing a similar goal, Wang et al.[1] attempt to understand the representation of odour and associated value information in the mouse cortex, focusing on the role of the piriform cortex (PC), orbitofrontal cortex (OFC) and medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC).

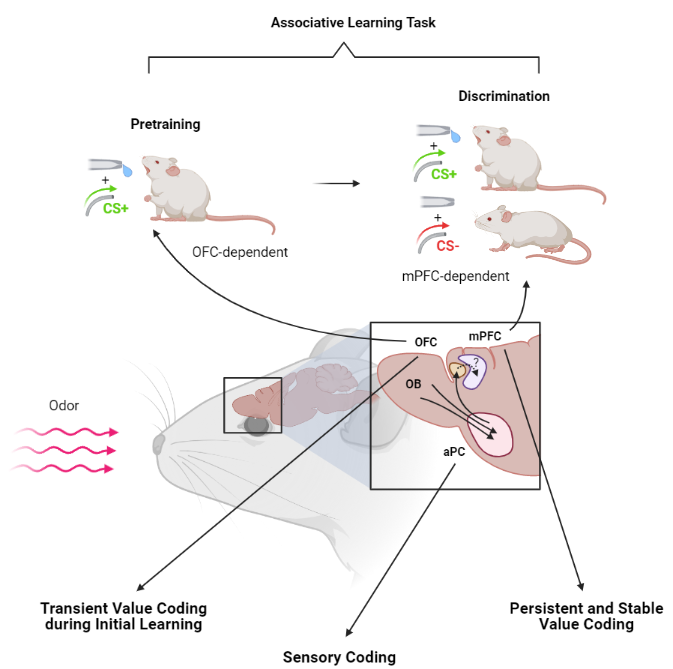

Using two-photon calcium imaging during training for a classical appetitive odour discrimination task, Wang et al. build upon the previously available corpus of information about the olfactory value coding system in mammalian models. Many of their results replicate some early observations about the nature of value coding in the rat PC and OFC.[2,3] Wang et al. further attempt to break down associative learning in mice into two-component processes—the initial association of modality to reward value (pretraining) and the second process of discriminating value associated with different stimulus within the modality (discrimination)—and link them to activity in distinct brain regions.

In line with previous studies[2], Wang et al. find that the PC is involved more in stimulus representation than value coding as the process of learning results in only mild changes in activity that were enough to improve linear separability of odour identity progressively. They associate most of the changes to passive exposure, not learning except for a rise in the excitatory power for the CS+ stimulus. It is important to note that the study focus is on the anterior piriform cortex (APC). Previous studies have suggested a more extensive value representation in the posterior piriform cortex (PPC), possibly due to more robust connectivity with the basolateral amygdala (ABL).[3] Thus this paper’s results cannot be directly extended to the entire piriform cortex.

Compared to the APC, the OFC representation was found to be a lot more plastic over training with odour-selective increases in excitation response and weak non-selective increases in inhibition. One fascinating observation was that it was easier to decode CS+ and CS- from the post-training population activity than decoding between two CS+ odours suggesting some form of generalisation unrelated to the licking response (which they show), that in this case is likely to be the internal representation of valence. To support this, they reversed the CS+ and CS- stimulus, which led to a reversal in responses of individual neurons in the OFC, making the population activity in response to the old CS+ indistinguishable from the new CS+ (old CS-) in line with Roesch et al.[2] who observed a reversal of selectivity and new selectivity in OFC neurons.

Context cues such as the absence of a reward port and internal states like satiety reduced the mean response of the OFC, further suggesting subjective value coding in the OFC. They confirmed the role of APC projections for the generations of the value representation by optogenetically activating a small subset of projections to OFC paired with water reward, which was enough to entrain the animals and perform anticipatory licking and optogenetic inhibition of the OFC was enough to prevent learning.

When they split the associative learning process into two parts: pretraining and discrimination, they found the only the initial seemed to depend on OFC activity in both head-fixed and freely moving assays. Disinhibition of the OFC was enough to allow learning in the pretraining phase. Supporting this further, CS+ learning during pretraining caused an increase in the mean response of the OFC population. But during the discrimination task, the responses started off non-selective, weak and indistinguishable had a transient increase in strength and CS+ specificity followed by a decay below the initial activity and a reduction in discriminability on overtraining.

In contrast to this, the mPFC presented a different value representation. Wang et al. found that the mPFC does not show a change in response during pretraining but shows two distinct ensemble activity states for CS+ and CS- during the discrimination phase. Further, optogenetically impaired mice show learning deficits during discrimination learning in both head-fixed and freely-moving mice. This representation lasts even after overtraining and can possibly act as a stable value representation compared to the transient response of OFC neurons during early training. Unfortunately, Wang et al. did not repeat the internal state, task context, and reversal experiments with the mPFC and did not establish the role of APC/OFC projections to the mPFC, which makes their results about the mPFC slightly less informative than the OFC.

While Wang et al. does present compelling evidence about different aspects of olfactory value coding in the prefrontal cortex, it opens up the ground for further questioning about the nature of the OFC itself. Is the value coded just a representation of learnt value, or is it associated with the prior experience and learning the task itself, and a predictive value code is just a consequence? Given the independence, sequential nature of the pretraining and discrimination tasks, and the OFC context-dependence, the OFC may have a function beyond odour value coding that may extend to generalised task learning. The authors propose a ‘teaching’ function of the OFC where the transient response in OFC entrains a more stable activity pattern in mPFC but this has not been explicitly tested. Further, how does the PFC integrate rewards signals from the midbrain with the odour identity and context cues over learning? If a parallel is drawn between the organisation of the mammalian PC, PFC, and ABL to the insect mushroom body, mushroom body output neurons and dopaminergic neurons respectively, is the activity-driven plasticity in the OFC reminiscent of the dopamine-driven learning in insects? All in all, Wang et al. certainly improves our understanding of distributed value coding in the PFC but ends with more questions to ask and answers to look forward to.

References:

[1] Wang, P. Y., Boboila, C., Chin, M., Higashi-Howard, A., Shamash, P., Wu, Z., ... & Axel, R. (2020). Transient and persistent representations of odor value in prefrontal cortex. Neuron, 108(1), 209-224.

[2] Roesch, M. R., Stalnaker, T. A., & Schoenbaum, G. (2007). Associative encoding in anterior piriform cortex versus orbitofrontal cortex during odor discrimination and reversal learning. Cerebral Cortex, 17(3), 643-652.

[3] Calu, D. J., Roesch, M. R., Stalnaker, T. A., & Schoenbaum, G. (2007). Associative encoding in posterior piriform cortex during odor discrimination and reversal learning. Cerebral cortex, 17(6), 1342-1349.]