Preparedness and Resilience

In the editorial article “Disaster resilience: a bounce back or bounce forward ability?”, the authors explore the idea of the disaster resilience paradigm as a distinct concept from the idea of vulnerability by reviewing the use of the paradigm in disaster literature and expressing their support for a newer framework of disaster resilience - the “bounce forward” approach. They claim that this approach reconceptualizes disaster response to incorporate the essence of structure and agency, temporality and continuity, and human psychology. Resilience and vulnerability have often been seen as “two sides of the same coin”, but the authors attempt to convince us that while they are both connected and to the underlying socio-political and economic factors of the affected society, they are distinct concepts and approach limits our understanding of resilience as “bounce forward” ability rather than the literal translation “bounce back” ability.

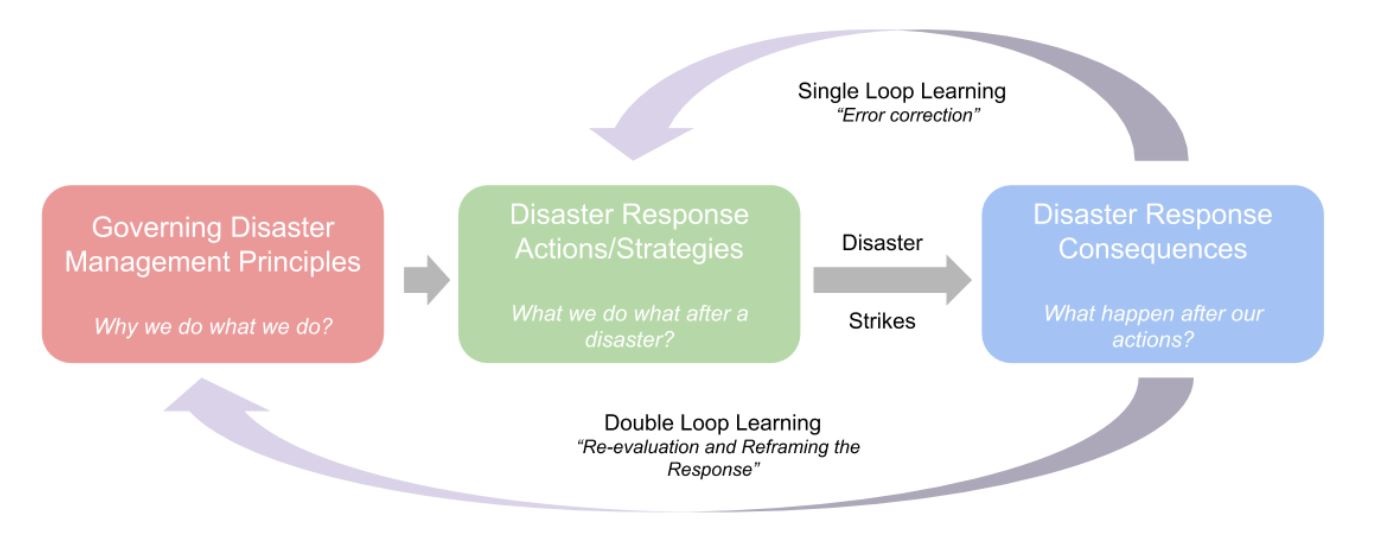

The authors supplement their claims with our understanding from human psychology that it is unlikely, if not impossible for human societies to return to an initial state as any perturbation brought to the social, political, and economic institutions by a disaster is not memoryless and will have a lasting historical effect on the social fabric. In this way, the “bounce back” approach fails to account for while the “bounce forward” approach utilizes the information from social change and builds an understanding of the ability of a community to “move on” after a disaster and also the ability to learn from the disaster. To further elucidate the latter principle, the authors use an example from the famous business theorist Chris Argyris‘s theories of action, namely the concept of single-loop and double-loop learning which is best illustrated by the following diagram. Essentially, the authors believe resilience is best understood by the ability to meta-learn from the situational context and attempt to correct the overarching structures rather than error correction to return to the original state.

Finally through two case studies, UK’s institutional shift from fire management to arson prevention task forces and Somalia’s shift away from unsafe housing and water supplies after a tsunami, and a commentary on multiple previous studies, the authors give examples of how disaster resilience can be assessed. One limitation that they fail to address is that the resilience of a community can only be assessed ex post facto, as one cannot be sure that a community once resilient will necessarily be the same in the long run or under different contexts. Finally, they conclude that while this formal framework is not extensively used but, in practice, there is evidence that disaster resilience building is already naturally implemented in societies as is clear from the case studies.

The study of the 1999 Orissa cyclone and its consequences by Thomalla and Schmuck, can be interpreted as a case study of disaster resilience building and changing preparedness of different disaster response related organizations (NGOs and Government Organisations) before and after the 1999 Cyclone in Orissa, a high disaster risk area, prone to wind damage and tidal surges from cyclonic storms. The authors report based on previous studies that despite the frequency of cyclonic storms in the Bay of Bengal, due to the unpredictability of the path taken by cyclonic storms and the frequency of false alarms, the members of the disaster-prone community rarely take the appropriate action until it is too late. The authors find that before the 1999 cyclone, the lack of clear information about the nature of the risks and the lack of experience were the major factors that led to insufficient preparedness. A large number of individuals were unaware or unsure if they were at risk despite getting cyclone warnings.

Before 1999, the government was mainly involved in providing warnings, financial support, rescues, and distribution of essentials after the disaster rather than improving preparedness. Since the last cyclone was long in the past, NGOs such as the Red Cross found it hard to get funding to prepare the community through the construction of shelters and training. After the cyclone of 1999, which led to an enormous death toll, there was a shift in responsibilities. The government failed to coordinate the support measures after the crisis, which led to the humanitarian missions becoming chaotic, and thus the NGOs formed a network (ODMM) for more coordinated and efficient actions. They also invested in the construction of more shelters and training to build long-term awareness. The government too invested in long-term resilience building and established the OSDMA, which resulted in the creation of a large number of multipurpose and economically-sustainable cyclone shelters, cyclone-proof schools, and houses. However, both GOs and NGOs faced issues of corruption and lack of coordination.

Finally, to assess the improvement in preparedness, the authors looked at the response to the November 2002 cyclone and found that the community was now much better prepared and was much less chaotic with people taking shelter much in advance, while the government failed to provide transparent information and clarification in time. Thus the community was able to ‘bounce forward’ quite well after the disaster of 1999.

References:

Manyena, Bernard, et al. (2011). Disaster resilience: a bounce back or bounce forward ability?. Local Environment: The International Journal of Justice and Sustainability 16.5: 417-424.